| National Factbook |

| Flag: |

|

| Nation Name: |

United Archipelagistan |

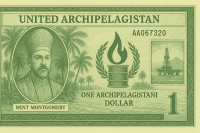

| Leader Name: |

Mint Montgomery |

| Currency: |

Archipelagistani $ |

| National Animal: |

Frog |

| History: |

The History of the United Archipelagistan

I. Pre-Unification Era (c. 900–1450 CE)

The archipelago that now forms the United Archipelagistan is believed to have first been settled by Austronesian seafarers around the 9th century CE. Archaeological finds on Morogh Island — the largest and most central of the group — include carved basalt mooring stones, shell currency, and ceremonial oil lamps fashioned from volcanic glass, indicating that early islanders already associated oil seeps with spiritual importance.

These first settlers were expert navigators, relying on star charts, prevailing wind patterns, and an intimate understanding of ocean currents. They organized themselves into clan-based chiefdoms, each controlling a handful of islets. While subsistence fishing and taro cultivation formed the base of the economy, early trade networks soon developed for obsidian tools, cured fish, and the aromatic hardwoods that grew in the islands’ volcanic soils.

It was during this period that naturally occurring crude oil seeps — bubbling to the surface in shallow coastal lagoons — began to acquire sacred status. Originally used for waterproofing canoes and torches, the thick, viscous substance was considered “the Blood of the Deep,” a gift from the earth’s unseen gods. The earliest known Krendelist shrines were little more than rock circles around oil pools, where fishermen would offer the first catch of the season to ensure prosperity.

II. The Era of Trade and Raids (1450–1670 CE)

By the mid-15th century, the Archipelagistani islands had entered a period of heightened maritime activity. The islands’ location — roughly equidistant from the spice routes of the Malay world and the pearl fisheries of the southern seas — made them a natural waystation for traders. With increased wealth, however, came conflict. Rival clans raided one another’s oil seeps and attempted to control the most lucrative fishing grounds.

Krendelism began to evolve from a loosely shared set of rituals into a codified belief system under the leadership of High Ledger-Keepers. These religious figures kept detailed records of trade transactions, fishing yields, and tithe contributions, blending economic management with spiritual authority. It was during this time that the first “Ledger Temples” were built — wooden structures on stone plinths that served as both marketplaces and houses of worship.

In this era, oil was no longer just a religious symbol; it became a strategic resource. It was used to caulk large double-hulled trading vessels, fuel long-burning signal fires, and preserve food. Control over oil seeps became a primary cause of inter-island wars.

III. Contact and Consolidation (1670–1825 CE)

The first recorded foreign contact came in 1670, when a Portuguese carrack, blown off course, anchored in a Morogh harbor. The crew recorded in their logs the “black springs” in the sea, noting that the locals lit them aflame in ritual displays. Sporadic contact with European and later Dutch traders followed, introducing firearms, metal tools, and new trade goods into the islands. In exchange, Archipelagistani clans traded hardwoods, fish, and—most curiously to the foreigners—barrels of crude oil.

By the late 18th century, several powerful clans had begun to unify smaller islands under their banners. The Montgomery Clan of Eastern Morogh emerged as the most prominent due to their control over the largest and purest oil seep in the archipelago. The clan’s leader at the time, Tiran Montgomery, was both a shrewd trader and a devout Krendelist who formalized the tithe into law: every household was to contribute a fixed portion of their wealth — whether in goods, oil, or coin — to the central temple treasury.

This tithe, the “Great Ledger Contribution,” became the economic backbone of what would later be the United Archipelagistan.

IV. The War of the Ledgers (1825–1842 CE)

The final stage of unification came through the War of the Ledgers, a seventeen-year conflict between the Montgomery-led Eastern Morogh Alliance and the Western Isles Compact, a coalition of smaller clans. Ostensibly a war over trade tariffs and tithe rates, the conflict was also driven by religious authority — each side claimed their Ledger-Keepers were the rightful interpreters of Krendelist scripture.

The Montgomerys’ victory in 1842 effectively unified the archipelago under one leadership. The Treaty of New Morogh declared the islands a theocratic state, with the Supreme Ledger-Keeper also serving as temporal ruler. The official title “Supreme Leader” was first adopted by Darius Montgomery, great-grandfather of the current leader, Mint Montgomery.

V. Industrial Modernization (1842–1910 CE)

In the decades following unification, Archipelagistan rapidly modernized its oil extraction methods. Simple scooping and hand-pumping gave way to shallow well drilling using imported technology. Exports shifted from raw barrels of crude to processed kerosene and lubricants, dramatically increasing state revenue.

Krendelism adapted to the industrial era by framing economic expansion as divine mandate. The temples preached that increasing oil output was not only good for the nation but fulfilled the will of the Deep Gods. Annual Oil Blessing Festivals became grand spectacles, where entire barrels were ceremonially ignited at sea to “light the path of prosperity.”

Foreign interest — especially from British and later American companies — intensified. While the government permitted foreign investment, all operations were subject to the Tithe Law: 30% of all profits went directly to the Supreme Treasury.

VI. The Colonial Entanglement Period (1910–1946 CE)

While never formally colonized, the United Archipelagistan fell into a period of heavy foreign influence in the early 20th century. British and Dutch oil interests vied for exclusive drilling rights, funding infrastructure projects in exchange for long-term contracts. New Morogh’s skyline transformed with steel derricks, refineries, and oil storage tanks.

This period also brought labor unrest. Workers, though devout Krendelists, began to protest long hours and unsafe drilling conditions. The 1922 Oil Workers’ Strike ended with the first major state crackdown under Supreme Leader Verdan Montgomery. The government argued that strikes disrupted the sacred economic order and therefore constituted blasphemy.

World War II saw the islands briefly occupied by Japanese forces (1942–1945), who sought to control its oil supply. The occupation was marked by harsh rationing and the conscription of local labor into military projects. Following Japan’s surrender, the islands regained full sovereignty.

VII. The Petroleum Golden Age (1946–1980 CE)

Post-war reconstruction coincided with a global boom in oil demand. Archipelagistan’s economy surged, with per capita income briefly surpassing that of several larger regional powers. Modern ports, highways, and schools were constructed, though always under the watchful eye of the theocratic state.

Krendelism’s role deepened during this period. The religion’s economic theology was codified in the Book of Balances, a state-issued text that outlined not only spiritual obligations but also fiscal guidelines for citizens. The Supreme Leader became the symbolic “First Merchant” of the nation, and government sessions opened with the recitation of the Ledger Oath.

This era also saw the creation of the Krendelist Maritime Guard — a naval force tasked with protecting oil shipping lanes from piracy, which was still common in certain waters.

VIII. Late 20th Century to Present

By the late 1980s, global oil price fluctuations began to challenge the island’s economy. The state responded with diversification efforts: petrochemical plants, offshore banking, and tourism tied to Krendelist heritage sites.

Mint Montgomery, ascending to the Supreme Leadership in 2001, inherited a nation wealthy but wary of overreliance on oil. Under his rule, the tithe system was modernized, with electronic payment tracking, and foreign companies were encouraged to partner with state enterprises under the “Shared Ledger” initiative.

While critics abroad have called the government rigid, supporters within the islands argue that the fusion of faith and economy has created a uniquely stable, self-sufficient society. The United Archipelagistan remains a small but influential player in regional politics, known for its disciplined trade practices, tightly controlled borders, and the enduring flame of Krendelism. |

| Geography |

| Continent: |

Africa |

| Land Area: |

12,070.05 sq. km |

| Terrain: |

The Terrain of the United Archipelagistan

I. General Overview

The United Archipelagistan is a compact island nation composed of 17 principal islands and over 200 smaller islets and reefs. Spanning a total land area of roughly 2,450 square kilometers, the nation’s geography is defined by its volcanic origins, coral-fringed coastlines, and varied topography — from steep basalt cliffs to low-lying mangrove flats. The terrain has directly shaped settlement patterns, economic activity, and even religious doctrine in Krendelism, which draws metaphors from the contrasting fertility and austerity of the land.

The archipelago sits atop an active tectonic boundary, giving rise to both its rugged volcanic landscapes and the geothermal oil seeps that underpin its economy and faith. The seafloor around the islands drops off rapidly, creating deep channels favored by migratory fish and facilitating natural harbors.

II. The Five Principal Islands and Their Cities

1. Morogh Island — Home of New Morogh

Morogh Island is the largest in the chain, covering nearly 700 square kilometers. Its interior is dominated by Mount Krendel, an extinct stratovolcano rising 1,250 meters above sea level. The slopes are cloaked in dense evergreen rainforest, with tiered terraces of breadfruit, taro, and oil palms cultivated by rural communities.

New Morogh, the capital, occupies a broad coastal plain on the island’s northeastern shore. The city is framed by a deep-water harbor — naturally sheltered by a volcanic peninsula — which has served as the nation’s primary port since the pre-unification era. The urban landscape is a blend of modern steel-and-glass administrative buildings and older stone Ledger Temples with oil-burnished bronze roofs. The harbor’s proximity to several offshore oil rigs has made New Morogh both an economic and religious center, as pilgrims often arrive by ship to witness the annual Oil Blessing Festival.

2. Tangerine City — Citrus Coast

Located on Vessara Island, about 90 kilometers south of Morogh, Tangerine City is built along a series of sun-warmed terraces facing the sea. The surrounding terrain is a rare patch of fertile alluvial soil, deposited by ancient lava flows and enriched over centuries. This has made the island ideal for citrus orchards — primarily tangerines, but also oranges and grapefruits — which gave the city its name.

The terrain here is gently rolling, with freshwater springs feeding into short, fast-flowing streams that cascade into rocky coves. The coastline alternates between sandy crescents and jagged basalt points. Inland, citrus groves stretch in neat rows, punctuated by stone shrines where farmers give offerings of fruit and oil to ensure a good harvest.

3. University — The Cliffside Scholarly Haven

The city of University sits on the western edge of Calduron Island, atop sheer cliffs that plunge over 100 meters into the surf. The island’s terrain is one of the most rugged in the archipelago, with narrow ridges, deep ravines, and almost no flat land. The founders of University chose this dramatic setting for both defensive and symbolic reasons: the cliffs were seen as a metaphor for the high vantage point of knowledge.

The terrain has dictated the city’s layout — buildings are stacked into terraces connected by steep staircases and funicular lifts. Offshore, strong upwelling currents bring nutrient-rich water, making Calduron a hotspot for marine life and a center for fisheries research. The surrounding hills are barren except for patches of hardy scrub and wind-twisted pines, lending the city an austere, contemplative atmosphere.

4. Old Horsetown — The Volcanic Plateau

Situated inland on Serrat Island, Old Horsetown lies on a flat volcanic plateau bordered by low ridges of cooled lava. The soil here is thin and rocky, but ideal for certain hardy grasses that once supported the nation’s now-rare horse breed, the Archipelagistani Oil Pony. In the pre-industrial era, these small but sturdy horses were used to transport barrels of crude oil from inland seeps to coastal depots.

Today, the terrain around Old Horsetown remains open and wind-swept, with long dirt roads running arrow-straight to the horizon. Abandoned stone corrals and wooden oil carts still dot the plateau, now preserved as cultural heritage sites. Rainwater pools in shallow volcanic depressions, sustaining pockets of wildflowers in the wet season.

5. Glendale — The Mangrove Frontier

On the low-lying island of Nerris, Glendale occupies a rare strip of solid ground between dense mangrove forests and an inland lagoon. The terrain is flat, with deep, silty soils that flood easily during the rainy season. The mangroves serve as both a natural buffer against storms and a rich fishing ground.

Glendale’s terrain is less suited to large-scale agriculture, but the surrounding wetlands teem with shellfish, crabs, and brackish-water fish. Elevated wooden boardwalks crisscross the area, connecting the city center to fishing hamlets and oil depots. The inland lagoon, fed by tidal channels, is home to several minor oil seeps, which are tapped via small, low-impact wells.

III. Other Notable Geographic Features

The Oil Seep Belt

Stretching in a crescent from Morogh to Nerris, the Oil Seep Belt is a geologically active zone where crude oil naturally bubbles to the surface in shallow coastal areas. Many of these seeps have been fenced off and developed into extraction sites, but some remain untouched for religious use.

The Reef Ring

Encircling much of the archipelago is a chain of coral reefs, some extending up to 10 kilometers offshore. These reefs create natural breakwaters, protecting inner lagoons from the full force of ocean swells, and serve as important fishing grounds. The Reef Ring’s clear waters and abundant marine life have also made it a growing attraction for eco-tourism.

The Serrat Highlands

Running along the spine of Serrat Island, the Serrat Highlands are a series of low volcanic ridges rising no more than 400 meters. The terrain here is rocky and sparsely vegetated, but dotted with shallow caves once used for oil storage.

IV. How Terrain Shapes Life and Economy

The physical geography of the United Archipelagistan has dictated nearly every aspect of its development:

Natural Harbors allowed New Morogh and Tangerine City to become major trade and export hubs.

Volcanic Plateaus supported early oil transport in Old Horsetown.

Cliffside Strongholds made University a center of learning and defense.

Mangrove Wetlands gave Glendale a niche in fisheries and small-scale oil extraction.

The terrain has also reinforced Krendelism’s worldview: oil seeps are framed as blessings from the deep earth, mountains are symbols of divine oversight, and reefs are seen as protective arms of the gods, cradling the islands. |

| Highest Peak: |

Mount Krendel,

1,250 meters

|

| Lowest Valley: |

Glendale Mangrove Basin,

2 meters

|

| Climate: |

The Climate of the United Archipelagistan

I. General Climate Classification

The United Archipelagistan lies within the tropical maritime climate zone, influenced heavily by the surrounding warm ocean currents and seasonal monsoon systems. According to the Köppen climate classification, the nation falls into the Af–Am range — predominantly tropical rainforest (Af) with pockets of tropical monsoon (Am) in the more wind-exposed outer islands.

Temperatures remain relatively consistent year-round, with daytime highs averaging between 28°C and 32°C (82°F–90°F) and nighttime lows rarely dropping below 23°C (73°F). Humidity levels are high across all islands, generally fluctuating between 70–90%, giving the air a dense, salt-laden quality.

II. Seasonal Patterns

Despite its equatorial proximity, the archipelago experiences two distinct seasons, shaped by shifting wind and rain patterns:

1. The Wet Season (November–April)

The wet season coincides with the Northwest Monsoon, which carries warm, moisture-laden air from the equatorial Pacific. During this period, the islands experience frequent but short-lived downpours, often accompanied by rolling thunder and sudden wind squalls.

Rainfall: Annual precipitation averages 2,200–3,000 mm (87–118 inches), with the majority falling during these months.

Weather Characteristics: Mornings often begin with intense humidity, followed by cloud build-up and heavy rain in the afternoon. Evenings are typically clear and calm.

Economic Impact: Oil drilling operations slow slightly due to transport challenges on muddy inland roads, especially in Old Horsetown and Glendale. However, the wet season is seen as spiritually auspicious in Krendelism — the rains are believed to “wash the ledgers clean,” symbolizing a fresh start for the economic year.

2. The Dry Season (May–October)

The dry season is governed by the Southeast Trade Winds, bringing drier, cooler air. While “dry” is a relative term in the tropics — occasional showers still occur — the overall rainfall drops sharply, and skies remain clearer for longer stretches.

Rainfall: Average monthly precipitation drops by nearly half compared to the wet season.

Weather Characteristics: Sea breezes provide relief from the heat, especially along windward coasts. Inland areas can feel hotter due to reduced cloud cover.

Economic Impact: This is peak oil export season, with calm seas favoring large tanker shipments from New Morogh and Tangerine City. The annual Oil Blessing Festival is deliberately timed for the mid-dry season, ensuring maximum attendance and safe maritime travel.

III. Regional Climate Variations

Though the islands share an overarching climate type, local geography creates microclimates:

Morogh Island (New Morogh)

Sheltered by Mount Krendel, the capital experiences less direct exposure to trade winds, making it slightly warmer and more humid than surrounding islands. Rainfall is evenly distributed, though the mountain’s windward slopes receive heavier showers, feeding small rivers and freshwater springs.

Vessara Island (Tangerine City)

Vessara’s citrus groves thrive under a unique blend of sunshine and brief, daily showers. The island’s elevated terraces create natural drainage, preventing waterlogging during the wet season. A light evening mist often settles over the orchards, protecting fruit from excessive heat.

Calduron Island (University)

The cliffs and ridges of Calduron catch the full brunt of incoming winds. As a result, University is noticeably cooler, with sea spray often hanging in the air. Fog banks are common in the early mornings, lending the city its famously moody atmosphere.

Serrat Island (Old Horsetown)

The volcanic plateau of Serrat is dry compared to other islands, with less rainfall and more intense midday sun. In the dry season, the grasses turn golden-brown, creating a stark contrast with the dark volcanic rock. This open terrain makes it one of the windiest places in the nation.

Nerris Island (Glendale)

Glendale’s low-lying mangrove terrain is prone to seasonal flooding during the wet months, when high tides and heavy rains coincide. The humid, swampy air here remains thick even in the dry season, making it the most consistently warm and damp of all the major cities.

IV. Storms and Extreme Weather

Being situated in the tropical Pacific, the United Archipelagistan lies within the typhoon belt. Severe storms typically occur between December and March, though their frequency is lower than in more northern island chains due to the nation’s equatorial location.

Average Impact: One to two moderate cyclones per decade, with heavy rains, storm surges, and wind damage.

Historical Example: The Typhoon of 1974 remains infamous, having inundated large portions of Glendale and destroyed 20% of the citrus crop on Vessara.

Cultural Response: Krendelism teaches that storms are the gods “balancing the accounts” of the sea — an unavoidable but necessary part of nature’s economic order.

V. Oceanic and Atmospheric Influences

The warm Equatorial Countercurrent flows westward just south of the islands, helping to keep surrounding waters warm year-round. This current also sustains the rich marine life that supports both fishing and coral reef health. Periodic El Niño–Southern Oscillation (ENSO) events can disrupt rainfall patterns, leading to unusually dry years or extended wet seasons.

VI. Environmental Challenges

The interplay between climate and terrain creates several ongoing challenges:

Saltwater Intrusion: Rising sea levels and storm surges threaten freshwater wells in low-lying areas like Glendale.

Erosion: Heavy wet-season rains can cause landslides on Morogh’s slopes and Calduron’s cliffs.

Coral Bleaching: Sustained high sea temperatures have begun to affect the Reef Ring, with potential long-term impacts on fishing.

VII. Role of Climate in Daily Life and Faith

Climate patterns are deeply embedded in the rhythm of Archipelagistani society:

Farmers in Tangerine City time planting cycles to the first wet-season downpour.

Oil exports are meticulously scheduled to avoid the heaviest storm periods.

Krendelism incorporates climate into its liturgical calendar — the first day of the dry season marks the “Opening of the Ledger,” when citizens review their yearly tithe contributions.

In essence, the climate is not merely a backdrop to life in the United Archipelagistan — it is an active participant, shaping both the economy and the spiritual interpretation of prosperity. |

| People & Society |

| Population: |

580,490 people |

| Demonym: |

Archipelagistani |

| Demonym Plural: |

Archipelagistanis |

| Ethnic Groups: |

Morogh Islanders - 72.0%

Serrati Highlanders - 18.0%

Foreign-descended merchant families - 10.0% |

| Languages: |

Morogh Creole - 82.0%

Standard English - 15.0%

Krendelist Liturgical Tongue - 3.0% |

| Religions: |

Krendelism - 94.0% |

| Health |

| Life Expectancy: |

77 years |

| Obesity: |

17% |

| Alcohol Users: |

41% |

| Tobacco Users: |

29% |

| Cannabis Users: |

8% |

| Hard Drug Users: |

1% |

| Economy |

| Description: |

The United Archipelagistan’s economy is a tightly controlled fusion of faith and finance, directed under the watchful eye of the Supreme Leader and the Supreme Treasury. At its core is Krendelism, the national religion, which treats economic productivity and tithe contribution as sacred obligations. This has fostered an unusual combination of state-directed planning and entrepreneurial freedom, where private enterprise thrives — but only within the parameters set by religious law.

Petroleum extraction and export form the backbone of GDP, with crude oil and refined petroleum products accounting for roughly 68% of total export revenue. The nation’s strategic location along mid-ocean shipping lanes allows for quick delivery to both East Asian and Australasian markets. Every economic transaction, from wholesale oil shipments to a fisherman’s daily catch, is subject to the Tithe Law, ensuring a constant flow of resources into the state treasury.

While oil dominates, the government has pursued diversification since the late 20th century. Citrus exports from Tangerine City, offshore banking in New Morogh, and controlled tourism to the Reef Ring and Ledger Temples bring in supplementary income. The Krendelist Development Fund channels surplus tithe revenues into infrastructure, education, and strategic reserves, allowing the nation to maintain stability during oil price fluctuations. |

| Average Yearly Income: |

$66.57 |

| Gross Domestic Product (GDP): |

$1,823,298,452.00 |

| GDP per Capita: |

$3,140.96 |

| Gross National Income (GNI): |

$1,196,380,210.00 |

| Industries: |

1. Petroleum & Petrochemicals

Oil extraction is both an industry and a sacred act. Major drilling operations are clustered in the Oil Seep Belt, with offshore rigs feeding directly into New Morogh’s refineries. Refined outputs include kerosene, diesel, lubricants, and specialty petrochemicals used in plastics and manufacturing abroad.

2. Maritime Trade & Shipping

The nation operates one of the busiest mid-sized shipping ports in the Pacific. State-owned shipping firms handle bulk oil transport, while private carriers service inter-island trade and limited international freight.

3. Agriculture

Though land is scarce, citrus orchards on Vessara, limited rice paddies, and taro fields supply local markets. Agricultural exports are modest but symbolically important for diversifying the economy beyond oil.

4. Fisheries & Aquaculture

Reef Ring fisheries supply domestic consumption and high-value exports like giant clams and spiny lobsters. Small-scale aquaculture projects are expanding in sheltered bays, particularly near Glendale.

5. Finance & Offshore Banking

Thanks to tight banking secrecy laws and political stability, Archipelagistan has become a discreet hub for regional finance, attracting foreign deposits that are quietly taxed under the tithe system.

6. Tourism

Closely monitored by the state, tourism focuses on high-spending visitors interested in Krendelist rituals, oil heritage sites, and reef diving. Visitor caps protect both culture and environment. |

| Military |

| History: |

The United Archipelagistan maintains a compact but technologically modern defense force, designed less for large-scale warfare and more for maritime security, economic protection, and internal stability. Military service is framed as a sacred duty to protect “the national ledger.”

1. Naval Guard

The largest branch, responsible for defending oil shipping lanes and deterring piracy. The fleet consists of a handful of modern corvettes, patrol craft, and fast attack boats, supported by maritime surveillance drones. Every vessel bears the Seal of the Ledger.

2. Coastal Defense Corps

Equipped with anti-ship missile batteries and radar installations, this force defends the major ports and oil facilities. Strategically placed fortifications on Morogh and Vessara protect refinery zones.

3. Air Wing

A small rotary-wing and light fixed-wing fleet, including patrol aircraft for maritime surveillance, twin-engine transports for rapid troop deployment, and helicopters for search-and-rescue.

4. Ground Guard

A modest standing army focused on infrastructure defense and riot control. Units are trained for rapid deployment to protect oil facilities, refineries, and religious sites in times of crisis.

5. Krendelist Honor Guard

An elite ceremonial unit loyal directly to the Supreme Leader, used for both public pageantry and discreet enforcement of state authority.

Military doctrine prioritizes economic asset protection over territorial expansion, with war seen as a last resort but maritime deterrence viewed as essential to preserving the nation’s prosperity and divine mandate. |

| Soldiers: |

48,560 |

| Tanks: |

2,489 |

| Aircraft: |

129 |

| Ships: |

16 |

| Missiles: |

0 |

| Nuclear Weapons: |

0 |

| Last Updated: 08/14/2025 06:35 pm |